Moving beyond the ivory tower: A model for promoting collaborations between researchers and communities to foster lasting change

By Neha J. Goel, B.A., Transdisciplinary Research Fellow

In the typical structure of a university, faculty members are limited to working with members of their own departments, corralled off in silos that effectively limit interdisciplinary communication and potential funding opportunities. In response to this trend, universities are now promoting a new form of research, known as interdisciplinary, or multidisciplinary, research, to foster collaborations and partnerships across these independent departments. Ideally, this type of research approach allows researchers from different disciplines to work together to solve a particular issue, applying their disciplines’ unique lenses and individual expertise to the task at hand.

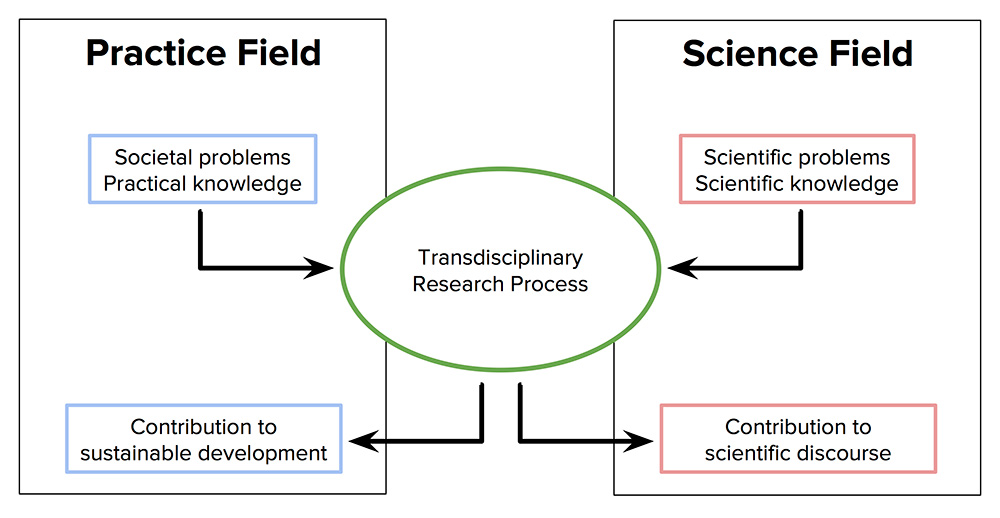

While this approach is moving in the right direction, there are still limits to the ways in which interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary research integrate and produce new knowledge. Alternatively, when institutions adopt policies that promote transdisciplinary research, which is problem-focused, collaborative, and a methodologically flexible approach to research (Wickson, Carew, & Russell, 2006), they are more likely to see lasting, impactful change. In contrast to multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary approaches, both of which transdisciplinary research overcomes the boundaries between scientific disciplines and promotes collaboration between both researchers and non-traditional researchers who bear unique forms of knowledge (e.g., policymakers, community leaders; Lang et al., 2012; Rosenfield, 1992; Wickson et al., 2006), In doing so, transdisciplinary research aims to address real-life, societal problems. As such, transdisciplinary approaches allow intensive, scientific research to leave the confines of the experimental laboratory of academia, or “ivory tower,” to be applied to and adapted for real communities who can benefit from this knowledge.

A model of the trandisciplinary research process

In light of the potential of transdisciplinary research, coupled with internal requests from faculty to provide opportunities for community-engaged research, the administration at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) in Richmond responded by developing and launching the Institute for Inclusion, Inquiry, and Innovation (iCubed) in 2016. iCubed is a cutting-edge institute focused on catalyzing collaborative connections between VCU and the community at large through innovative academic and research programs. Our own brand of transdisciplinary research aims to tear down the basic assumptions of research by asking community members to help us develop holistic solutions to 21st century urban challenges within the Commonwealth of Virginia and beyond. In order to accomplish this mission, iCubed is guided by four cardinal goals: (1) broaden access to education for students of diverse backgrounds; (2) create an inclusive environment for diverse faculty; (3) catalyze connections within the university community and with different local communities throughout Richmond; and (4) accomplish these tasks through the application of transdisciplinary research. iCubed is structured in such a way that faculty members who are interesting in solving a particular problem (e.g., oral healthcare, health and wellness in aging populations) can submit a proposal and form a transdisciplinary “Core” coalition. In response to faculty desire, iCubed currently boasts seven transdisciplinary Cores, each consisting of a range of undergraduate and graduate students, post-doctoral fellows, visiting scholars, research faculty, and community leaders.

As noted earlier, given that one of the main foci of transdisciplinary research is to benefit people outside of the academic sphere, community involvement is key to successful applications of transdisciplinary knowledge. As we see it, simply adopting a transdisciplinary approach to research does not resolve the issue of the “unidirectional transfer of knowledge,” such that scientists are only transmitting information to society, rather than a bilateral exchange of knowledge (Whitmer et al., 2010). Thus, in order to maximize the impact of research in a way that effects lasting change within a community, researchers are encouraged to collaborate and include community members within the research process, whether it be something as minimal as asking community members to vet researcher’s interpretations of the data through a process called “member-checking” (Creswell & Miller, 2000; Creswell & Poth, 2018), or as intensive as involving community members in every stage of the research design process (i.e., community-based participatory research [CBPR]; Wallerstein & Duran, 2010; Whitmer et al., 2010). Although community-engaged research methods are quite labor, resource, and time-intensive, when administered correctly, they have the potential to create sustainable partnerships, lasting change within a community, and a successful union between an institution and its constituents. For these reasons, much of the work that iCubed researchers conduct is focused on community engagement with different communities throughout Richmond.

In order to foster successful engagement between faculty, students, and community members, universities are encouraged to provide “mentoring, leadership training, networking, technical support, and innovative curriculum development” (Whitmer et al., 2010, p. 314). Similar to this approach, iCubed’s mission is to be a driving force for research through curriculum transformation (e.g., inclusive teaching, expanded pedagogy), to remedy inequities in healthcare access and treatment, and narrow the gap between access and opportunity for undergraduate students from underserved communities. As such, leaders at iCubed have crafted specific initiatives that uphold each of these tenets. These initiatives include a paid research mentorship program that matches students of the highest need and talent with premiere research faculty to prepare students for their professional careers beyond VCU, known as our Commonwealth Scholars Program, providing community forums in which iCubed faculty share their experiences about how their personal lives have impacted their research careers with the public, and regular faculty engagement via monthly meetings that foster transdisciplinary collaboration, community engagement, inclusivity, and social innovation. Taken collectively, iCubed pairs eager faculty with knowledgeable community leaders to effect lasting change both within and beyond Richmond.

In these ways, iCubed serves as a paradigmatic model for acknowledging the needs of both faculty researchers and individuals within local communities by fostering partnerships between these two groups. In doing so, iCubed acknowledges that surrounding Richmond communities are bearers of unique knowledge that are important groups to consider and collaborate with, and as such, should have an equal say at the intellectual table. Considering that local communities are affected, both directly and indirectly, by the actions of a university (Thrift, 2011), iCubed addresses this ethical dilemma by inviting communities to be active participants and agents of change, placing these communities at the center of the institute. In this unique way, iCubed is committed to moving beyond the traditional research framework by acknowledging that research can be purposeful, solution-focused, and impactful when the communities it aims to serve are central to the research methodologies and practices.

In sum, we present iCubed as a model for other research-oriented universities that are interested in pairing faculty with community members to effect change. By capitalizing on VCU’s signature motto that we can attain “national prominence through local impact,” we hope to inspire other urban institutions to adopt and adapt similar structures for their faculty, students, and surrounding communities.

For more information about iCubed or transdisciplinary research, please contact Neha Goel, iCubed’s Transdisciplinary Research Fellow and Co-Director of the Commonwealth Scholars Program, at goelnj@vcu.edu.

To cite this article: Goel, N.J. (2019, January). Moving beyond the ivory tower: A model for promoting collaboration between researchers and communities to foster lasting change [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://icubed.vcu.edu/research/

References

- Creswell, J.W., & Miller, D.L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Into Practice, 39(3), 124-130. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2

- Creswell, J. & Poth, C.N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th Ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Lang, D.J., Wiek, A., Bergmann, M., Stauffacher, M., Martens, P. Moll, P., …, & Thomas, C.J. (2012). Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: Practice, principles, and challenges. Sustainability Science, 7, 25-43. doi: 10.1007/s11625-011-0149-x

- Rosenfield, P.L. (1992). The potential of transdisciplinary research for sustaining and extending linkages between the health and social sciences. Social Science & Medicine, 35(11), 1343-1357.

- Thrift, N. (2011). The effect of students on university towns: A negative or positive? [News article]. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/blogs/worldwise/the-effect-of-students-on-university-towns-worldwide-a-negative-or-positive/28763

- Wallerstein, N., & Duran, B. (2010). Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: The intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health, 100, S40-S46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036

- Wickson, F., Carew, A.L., & Russell, A.W. (2006). Transdisciplinary research: Characteristics, quandaries and quality. Futures, 38, 1046-1059. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2006.02.011

- Whitmer, A., Ogden, L., Lawton, J., Sturner, P., Groffman, P.M., Schneider, L., …, & Killilea, M. (2010). The engaged university: Providing a platform for research that transforms society. Front Ecol Environ, 8(6), 314-321. doi: 10.1890/090241